What you need to know

As the COVID pandemic began to recede in 2021, Americans noticed rising prices throughout the economy, from groceries to gasoline, utility bills, and house prices. Rising prices reduce consumer and business confidence and make it harder for people to make ends meet. What is inflation, what causes it, and what can the United States government do about it?

What is Inflation?

Inflation occurs when the price of goods and services increases over time. As inflation rises, the same amount of money buys fewer goods and services. For example, suppose gasoline costs $3.00 per gallon in January. At this price, it costs $36.00 to fill a 12-gallon gas tank. Now suppose inflation causes gas prices to increase by 10% by December. Now gasoline costs $3.30 a gallon, and the same $36.00 will buy only 11 gallons.[1]

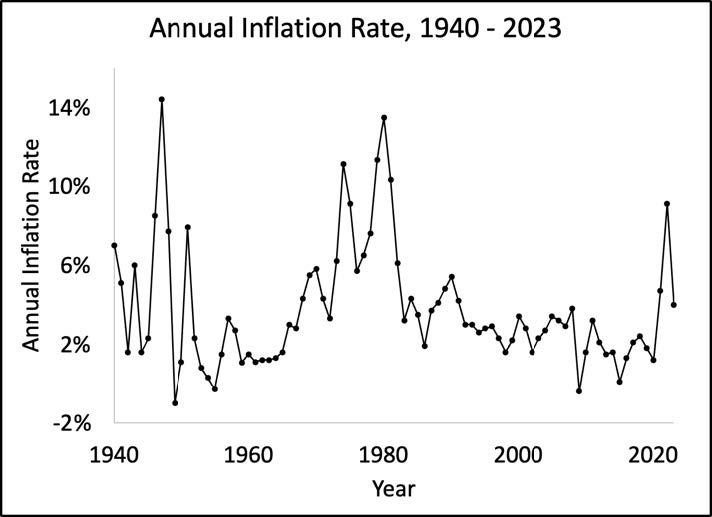

The figure below shows the annual inflation rate (inflation measured over a year) from 1940 through 2022. Over this time, the typical inflation rate has been about 2%, although there have been periods of much higher inflation. After the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation increased to an annual rate of 7.1% in 2021 and 6.5% in 2022. The highest inflation rate post-World War II occurred in the 1970s, when increased oil prices led to overall inflation rates of over 14%.[2]

What Causes Inflation?

There are two types of inflation: cost-push and demand-pull. Cost-push inflation is price changes caused by unexpected economic, social, or political developments. For example, when supply shortages increase production costs, companies raise prices to maintain profits. The next charts on the left show how in the 1970s, cost-push inflation occurred because oil-producing countries cut back on oil exports. This decrease in supply for a product in high demand created more competition for oil and resulted in its price quadrupling in 1973 and doubling again in 1979, leading to price increases throughout the economy.[3]

Demand-pull inflation occurs when unexpectedly high consumer or business demand for goods and services allows sellers to increase profits by raising prices. An example of demand-pull inflation occurred during the COVID pandemic, as shown in the two charts on the right-hand side of the page. Federal COVID assistance payments to individuals and businesses in 2020, 2021, and 2022, along with reductions in spending from staying home due to lockdowns, gave people more money to spend, which increased demand for goods such as laptop computers and home improvements. This abrupt shift in demand created a supply shortage of many products, from computer chips to lumber, causing prices to skyrocket.[4]

How is Inflation Measured?

The most commonly used measure of inflation is the Consumer Price Index (CPI). To find the change in prices over time, the CPI samples the price of various goods, like a pound of cheddar cheese or a gallon of gas, or services, like hiring a plumber. The prices of those samples are tracked over time.

Then, the CPI estimates the importance of each of these goods or services to the average consumer and weighs the price changes to see how much a consumer is paying overall. The figure below shows the CPI’s estimate for how much of an average consumer’s total spending is dedicated to different categories.[5]

There are some limits to using the CPI to measure inflation. For one, individual experience of inflation may vary drastically from the CPI estimate, since any one consumer’s spending might be divided differently than the calculations shown in the figure. The CPI also only tracks inflation from a consumer’s perspective. Other indices track inflation from the perspective of producers, employers, or even governments. For general purposes, though, the CPI is accepted as the best estimate for the average person.[6]

Alternatives to the CPI include the core CPI, which excludes food and energy prices because they often have sharp but temporary price changes. The CPI may also overstate inflation because it does not consider how people change behavior when prices rise (as beef prices increase, people eat less beef and more chicken). A third measure, the personal consumption expenditures (PCE), accounts for these changes by collecting data from businesses instead of consumers.[7]

Why Does Inflation Matter?

As inflation increases, purchasing power, or the amount of goods and services that can be bought with a fixed amount of money, decreases. Inflation also affects the interest rates people pay for mortgages, car loans, and other consumer credit.

As the chart below shows, increased inflation in 2021 and 2022 caused 30-year mortgage rates to roughly double. High inflation also creates uncertainty, making it harder for businesses to plan expansions and making individuals cautious about large purchases such as a home or a car. Both effects can lower economic growth.[ 8]

The impact of inflation disproportionately affects low-income individuals and families, who generally spend a greater percentage of their wages on necessities. In contrast, wealthier individuals and families spend more of their income on luxury goods, which they can reduce purchases as prices rise. The next chart shows that over the last 20 years, the inflation rate experienced by low-income families was significantly higher than that experienced by high-income families. Wealthy individuals also often have more savings to help handle periods of economic difficulty. [9]

Can Inflation Be Controlled?

Inflation is not easily or exactly controlled. One intuition is that when inflation happens, the government should print and distribute enough extra money so that everyone can buy the same amount of goods and services they could in the past before prices increased. The problem is, giving out money would lead to increased demand, creating additional demand-pull inflation and making the problem worse.

In the federal government, the primary responsibility for controlling inflation falls to the Federal Reserve Bank (Fed). The Fed’s main mechanism for controlling inflation is changing the federal funds rate (FFR). Raising the FFR increases the interest rate that banks nationwide charge for loans, mortgages, and consumer credit. The next chart shows how the Fed increased the FRR over the last two years. Increasing the FFR means it is more expensive to borrow money, so people are incentivized to save, and businesses cut back on expansion plans. As a result, spending by individuals and businesses decreases, and prices fall (or do not increase as much). Conversely, lowering the FFR decreases interest rates, making borrowing cheaper, so people spend more, and businesses expand. Increased spending by businesses and consumers means increased demand. Prices then rise to meet increased demand, leading to higher inflation.[10]

Although a high FFR might lower inflation, the rise in interest rates slows the economy, and businesses see a general decrease in revenue. These changes mean fewer hires and more layoffs. Therefore, in general, raising the FFR decreases inflation and increases unemployment, while lowering the FFR increases inflation and decreases unemployment. By law, the Fed’s policy goals are to maximize employment and minimize inflation. In practice, these goals have been interpreted as an unemployment rate of 4% or lower and an inflation rate of about 2%.[11]

Efforts to lower inflation by raising the federal funds rate involve a short-term vs. long-term tradeoff. In the short-term, most individuals and businesses are hurt by higher interest rates, reduced economic growth, and increased unemployment. In the long term, controlling inflation increases economic growth, which is good for most individuals and businesses. For example, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the Fed moved aggressively to curb inflation, unemployment reached 10.8%, interest rates for 30-year home mortgages were over 15%, and economic growth was negative. The Fed’s efforts were successful, leading to economic expansion and lower unemployment beginning in the mid-1980s.[12]

Changes in federal spending also affect the inflation rate. By increasing spending, Congress and the President can cause demand-pull inflation. In the same way, reducing (or limiting increases) in spending can reduce inflation. However, controls on spending have the same short-term vs. long-term tradeoff. In the long run, all Americans benefit from lower inflation, but in the short term, spending curbs can reduce federal benefits for individual Americans, particularly low-income individuals.[13]

Why not bring inflation down to zero?

Analyses indicate that economic growth is highest given low but not non-zero inflation rates (2-3%). Furthermore, if inflation dips too close to zero, the Fed will no longer be able to prevent or mitigate economic recessions by lowering the FFR to encourage employment and spending.[14]

Enjoying this content? Support our mission through financial support.

Further reading

- Ceyda, O. 2022. Inflation: Prices on the Rise. International Monetary Fund, accessed 1/27/23, available

at imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/Series/Back-to-Basics/Inflation - Harker, P. 2022. Inflation: What Caused it and What to Do About it? Philadelphia Federal Reserve,

accessed 1/23/23, available at tinyurl.com/3xekfjwv - Jaravel, X. 2021. Inflation Inequality: Measurement, Causes, and Policy Implications. Annual Review of

Economics, 13(1), 599–629, available at tinyurl.com/5n779nfs - Labonte, M. 2023. Introduction to the U.S. Economy: Monetary Policy. Congressional Research Service,

accessed 1/15/23, available at crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11751 - Weinstock R, L. 2022. Back to the Future? Lessons from the “Great Inflation.” Congressional Research

Service, accessed 1/27/23, available at crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12177

Sources

Definition of Inflation

- Oner, C. 2022. Inflation: Prices on the Rise. International Monetary Fund, accessed 1/27/23, available at

tinyurl.com/8nducu5j - Labonte, M., & Weinstock R. 2022. Inflation in the U.S Economy: Causes and Policy Options.

Congressional Research Service, accessed 1/23/23, available at tinyurl.com/mvjtmks9

Recent and Historical Inflation Rates

- Weinstock R, L. 2022. Back to the Future? Lessons from the “Great Inflation.” Congressional Research

Service, accessed 1/27/23, available at tinyurl.com/jxuz8z7w - Binder, C., & Kamdar, R. 2022. Expected and Realized Inflation in Historical Perspective. The Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 36(3), 131–156, available at jstor.org/stable/27151257

Cost-push inflation

- Church, J. D., & Akin, B. 2017. Examining price transmission across labor compensation costs, consumer prices, and finished-goods prices. Monthly Labor Review, 1–24, available at jstor.org/stable/90007786

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2023. Petroleum & Other Liquids. U.S. Energy Information

Administration, accessed 2/2/23, available at tinyurl.com/2p9ajhec

Demand-pull inflation

- Office of Management and Budget. 2022. Historical Tables. The White House, accessed 02/2/23,

available at whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/historical-tables/ - Oner, C. 2023. Inflation: Prices on the rise. International Monetary Fund, accessed 2/1/2023, available at

tinyurl.com/3skvjh38 - Waterhouse, B. C. 2013). Mobilizing for the Market: Organized Business, Wage-Price Controls, and the

Politics of Inflation, 1971-1974. The Journal of American History, 1002), 454–478, available at

jstor.org/stable/44307341 - Soyres, F., Santacreu, A.M., & Young, H. 2022. Fiscal policy and excess inflation during Covid-19: a cross-

country view. The Federal Reserve, accessed 2/8/23, available at tinyurl.com/39k2ft3y

The CPI

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. Consumer price index frequently asked questions, U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, accessed 2/10/23, available at bls.gov/cpi/questions-and-answers.htm - U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. The consumer price index-why the published averages don’t

always match an individual’s inflation experience. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed 2/10/23,

available at tinyurl.com/4nnkf67e

Measuring inflation

- Salwati, N., & Wessel, D. 2021. How does the government measure inflation? Brookings Institution,

accessed 2/2/23, available at tinyurl.com/53dnzvmf - Roncaglia de Carvalho, A., Ribeiro R, S, M., & Marques A, M., 2021). Economic development and

inflation: a theoretical and empirical analysis. International Review of Applied Economics. 32(4), 546-565.

Alternate measures

- Salwati, N., & Wessel, D. 2021. How does the government measure inflation? Brookings Institution,

accessed 1/15/23, available at tinyurl.com/2p9xbe9r - Knotek II, E & Rich W. 2022. Inflation Q & A, accessed 2/10/23, available at tinyurl.com/49d6m5tk

Impact of inflation

- Brunnermeier, M. K., & Sannikov, Y. 2016). On the Optimal Inflation Rate. The American Economic

Review, 106(5), 484–489, available at jstor.org/stable/43861068 - Economic Research Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2023. 30-Year Fixed Rate Mortgage Average in the

United States. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accessed 2/8/23, available at tinyurl.com/yc5dphma

Lower vs. Higher-Income

- Stockburger, J. K. & A. (2022) Inflation Experiences for Lower and Higher Income Households: Spotlight

on Statistics. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed 2/2/23, available at tinyurl.com/mrztdyc4 - Federal Reserve. 2020. How does the Federal Reserve aim for Inflation of 2 percent over the longer run?

Federal Reserve, accessed 1/17/23, available at tinyurl.com/2wtjvp7d

Controlling Inflation

- Labonte, M. 2023. The Federal Reserve and Inflation. Congressional Research Service, accessed 1/30/23,

available at crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11868 - Federal Reserve. 2022. Monetary Policy report. Federal Reserve, accessed 2/1/23, available at

tinyurl.com/bdfshfhx

Inflation policy targets

- Yellen, J. L. 2017). Inflation, uncertainty, and monetary policy. Business Economics, 52(4, 194–207,

available at jstor.org/stable/45208998 - Agarwal, R. and Kimball, M. 2022. How Costly is Inflation? International Monetary Fund. Accessed

1/23/23, available at tinyurl.com/2bkx6f38 - Ball, Laurence, et al. 2022. Understanding US Inflation during the COVID Era. Brookings Institute,

accessed 2/3/23, available at tinyurl.com/mpa6zdwz

Cost of controlling inflation

- Gilchrist, S., Schoenle, R., Sim, J., & Zakrajšek, E. 2017. Inflation Dynamics during the Financial Crisis. The American Economic Review, 107(3), 785–823, available at jstor.org/stable/44250313

- Kryeziu, & Durguti, E. A. 2019. The Impact of Inflation on Economic Growth: The Case of Eurozone.

International Journal of Finance & Banking Studies, 8(1), 1–9.

Federal Spending and Inflation

- Kimberlin, S. 2016. The Influence of Government Benefits and Taxes on Rates of Chronic and Transient

Poverty in the United States. Social Service Review, 90(2), 185-234, available at

jstor.org/stable/26463046 - Waterhouse, B. C. 2013. Mobilizing for the Market: Organized Business, Wage-Price Controls, and the

Politics of Inflation, 1971-1974. The Journal of American History, 1002, 454–478, available at

jstor.org/stable/44307341

Why not zero inflation?

- Akerlof, G. A., Perry, G. L., Dickens, W. T., 1996. Low Inflation or No Inflation: Should the Federal Reserve Pursue Complete Price Stability. Brookings Institute, accessed 2/9/23, available at tinyurl.com/ht9t5hk5

- Roncaglia de Carvalho, A., Ribeiro R, S, M., & Marques A, M., 2021. Economic development and inflation:

a theoretical and empirical analysis. International Review of Applied Economics. 32(4), 546-565 - Ahmmed, Uddin, M. N., Rafiq, M. R. I., & Uddin, M. J. 2020. Inflation And Economic Growth Link – Multi-Country Scenario. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 10(4): 47-48

- Federal Reserve. 2022. Why Does the Federal Reserve aim for Inflation of 2 percent over the Longer

Run?, accessed 1/23/23, available at tinyurl.com/2ytfxefc

Contributors

- This policy brief was researched and written in January-February 2023 by Policy vs. Politics interns RianaBucceri, Greta Filor, Raegan Gautam, Sarah Hanna, Jordyn Ives, Nithin Krishnan, Nick Markiewicz, AditiMenon, Zul Norin, Eli Oaks, Shelby Richardson (Rosa Nice), and Mary Stafford, with Dr. William Bianco.